I’ve just finished researching a whitepaper on luxury travel ahead of launching our exciting Luxperience MyTravelResearch.com luxury travel research. So I was really delighted when Australian public broadcaster SBS showed a two-part story from the BBC/Tern Television on ‘The Story of Luxury’. It’s one of the nice things about being a researcher is that business and pleasure so often intermingle.

The series starts with concepts of luxury from Ancient Greece and then looked at how these evolved both there and in the European Middle Ages. It was clearly Eurocentric (the history of luxury in Persia, India, and China among others would have made it even better). But in every other way, it proved to be a perfect context setting for my whitepaper.

Indeed, it nicely proved how much the old French saying ‘plus ça change, plus c’est la meme chose’ (or the more things change, the more they stay the same).

Definitions of luxury have been influenced by broader social and economic trends for at least 6,000 years

In Ancient Greece, the aristocracy of Athens responded to public pressures around ostentatious displays of wealth by shifting their ways of measuring luxury. They focused on acts of public charity (including providing meat for hungry pilgrims), on items of beauty, and on culture. This exactly parallels a trend seen in modern luxury travel away from the ostentatious display and ‘bling’ to a more experiential focus. This is also happening at a time of great economic change and concerns about rising levels of inequality.

Technology is a key influence on what constitutes luxury travel

Similarly in the Middle Ages, technological changes like the introduction of the printing press changed definitions of luxury. Prior to that books were an ‘ultra’ luxury product owned by very few: royalty, and a few wealthy monasteries. But the creation of the printing press made books an ‘accessible luxury’ for a new class of wealthy merchants. They were still luxury items but the proportion of people who could use and access them grew dramatically. Again today we see a rising affluent middle class and changing technologies changing definitions of luxury. Thanks to AirBnb you can now stay in a castle in Europe for as little as AUD156 (USD115) per night. Virgin Galactic is similarly taking space travel from the domain of multi-millionaires to that of the merely affluent. (It is also a powerful statement of Virgin’s position as a challenger brand – but that’s another story.)

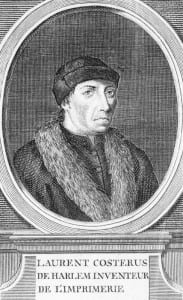

Technology change has ALWAYS driven perceptions of luxury: Laurens Janszoon Coster (1370-1440) Inventor of the printing press

It is clear that there are some cyclical trends in luxury travel. Hedonistic travel has not really gone away – if you doubt that check out the Burj Al Arab or the Lobanov Presidential Suite at the Lion Hotel in St Petersburg and at some point it may be once more the centre of luxury.

What are the implications for current and potential luxury travel businesses?

But two other practical considerations for those in or considering entering the luxury travel sector stand out.

Firstly, you need to know what kind of luxury you are planning to target: both in terms of the needs your luxury traveller has (hedonistic vs. experiential) and in terms of how luxurious (ultra-luxury, accessible luxury) the target market wants.

Secondly, it really stood out to me that luxury travel is a paradox. The experiences are rarer, more unusual, and more expensive. But trends in luxury travel are not cocooned from those in the wider world. Instead, they often predict it or reflect it. So if you are future-proofing your investment in luxury travel it is vital that you know your broader trend and travel landscape.

In that sense, luxury travel both is and isn’t unique.

Leave a Reply